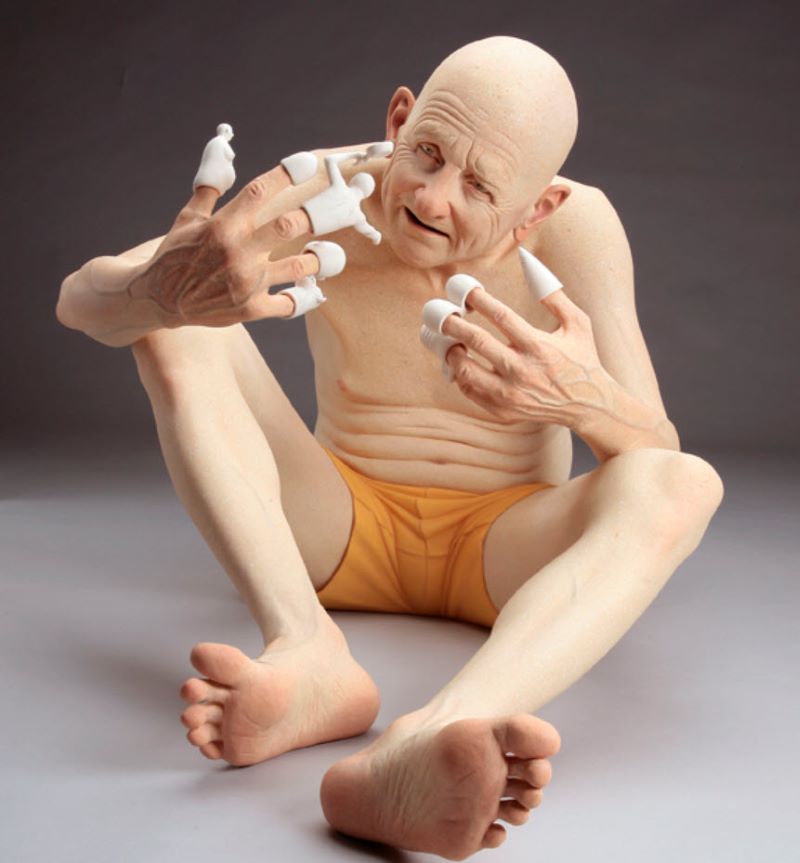

Gail Kendall is a former academic and maker of sumptuous pieces that reflect a deep interest in both form and surface. Her work also reflects a basic creative impulse to create objects of beauty and pleasure that add to our cultural tradition. I respect that impulse – deeply respect that impulse. A life spent adding beauty to the world is a life well spent.

JW: You note influence from 13th – 18th C. European pottery traditions. Where did you first encounter these ceramic traditions and how did you come to incorporate them into your work?

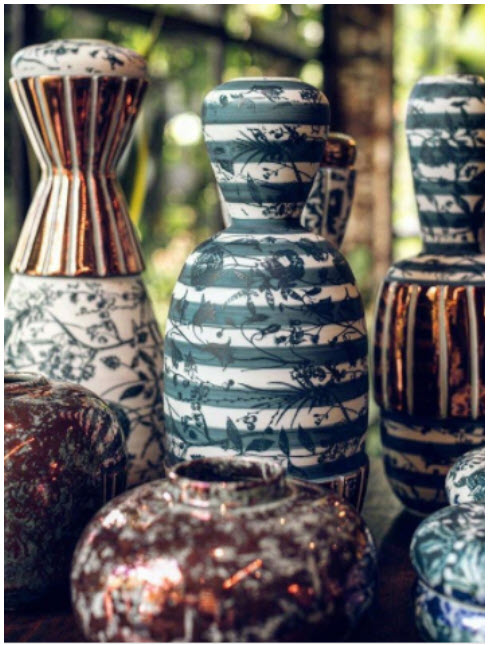

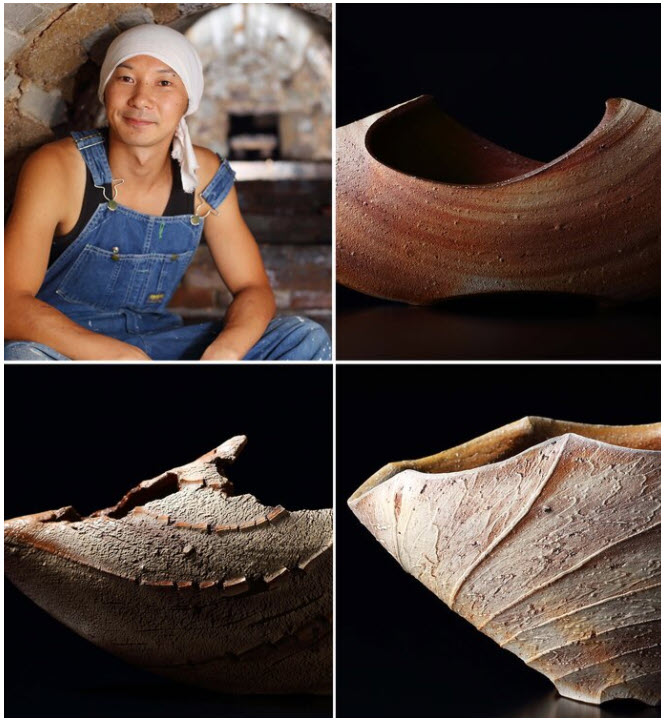

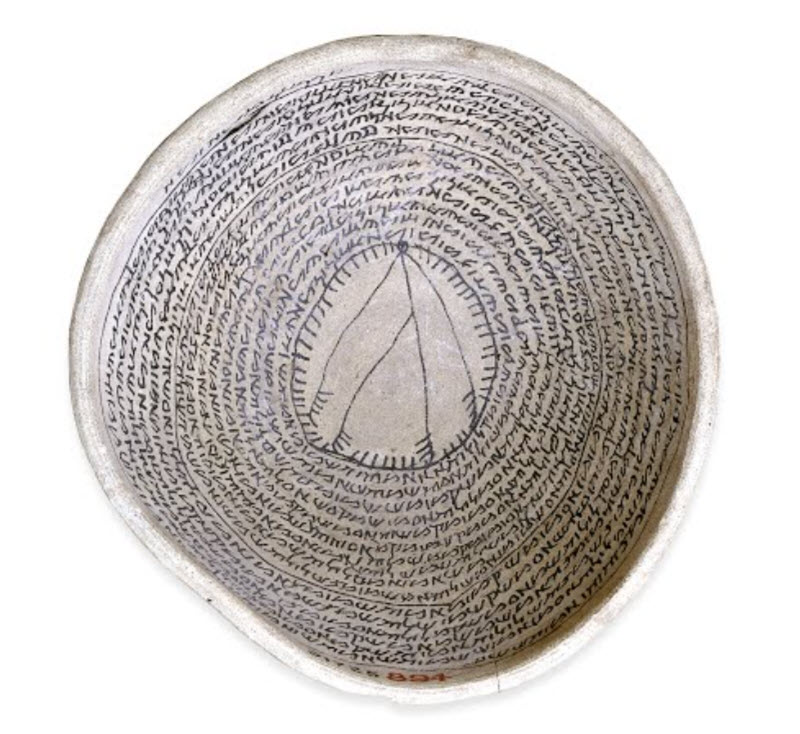

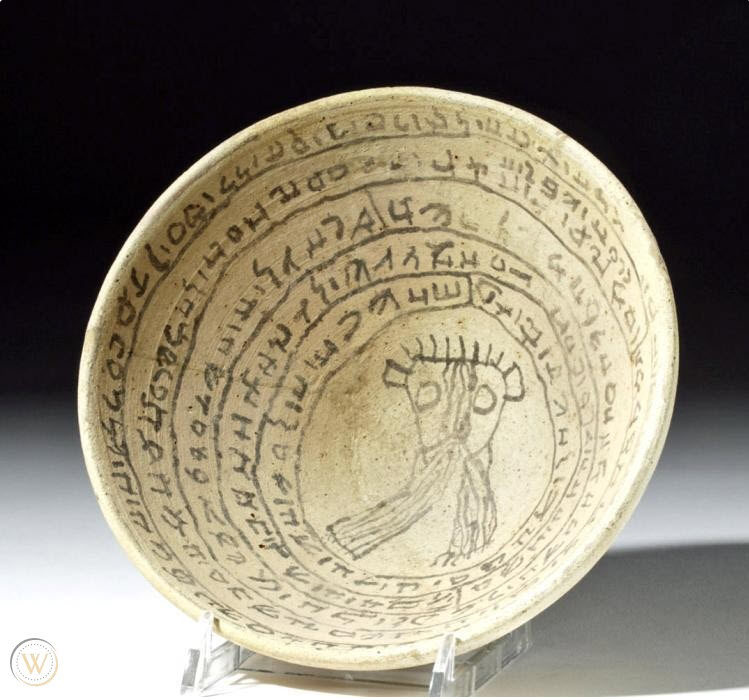

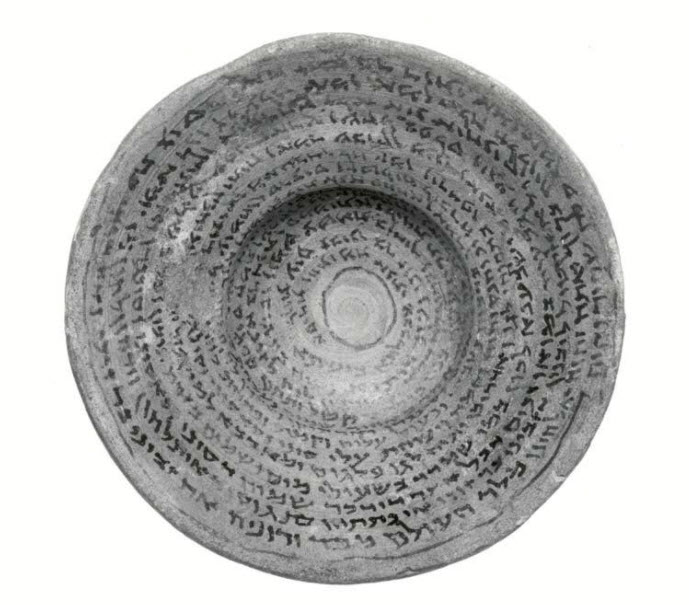

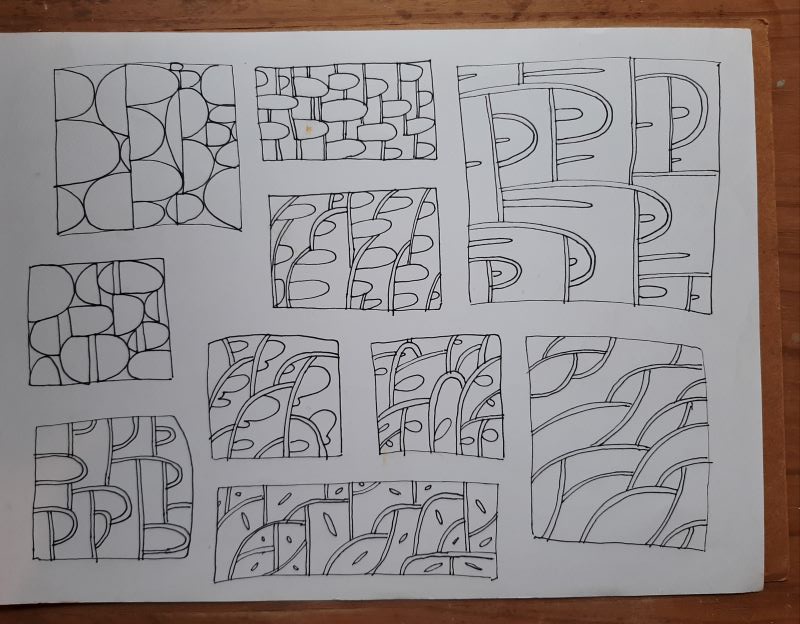

GK: The pots I turn to the most are historical. At one time, it was primarily surface on historical pots that I sought out and perhaps interpreted. Of late, I am looking at the simple volumetric forms that are to be found in every culture that has produced pottery. I have to admit I sometimes feel I am not stretching or challenging myself with more complex forms: particularly when I look at the work of my peers. Ultimately, I make what I am impelled to make and what gives me pleasure. If I were forced to defend my love of classic pottery form, I could say that my complex surfaces require them.

I believe that all artists, regardless of medium are made vulnerable in terms of their creative process. We pull original works from our guts and heart and put them out there, one way or another, to be judged, critiqued, talked about, cared about, or not. I think it was this stress that took me out of the studio. During the pandemic I knit four sweaters, baked sour dough bread, and cooked.

I shut down my creative work for the entire lock-downed part of the pandemic. That is 15 months or so. Why? I haven’t exactly figured that out. I can’t explain it especially when my potter pals were happy as clams and working day and night. I was not and still am not fearful or afraid of the virus. I take care but I grocery shop, visit friends who are part of my “quarantine pod” and in February ‘21 traveled to teach a workshop. On some level I must have dealt with enough stress about the lock-down (and let’s not forget the politics) that working in the studio had to take a vacation.

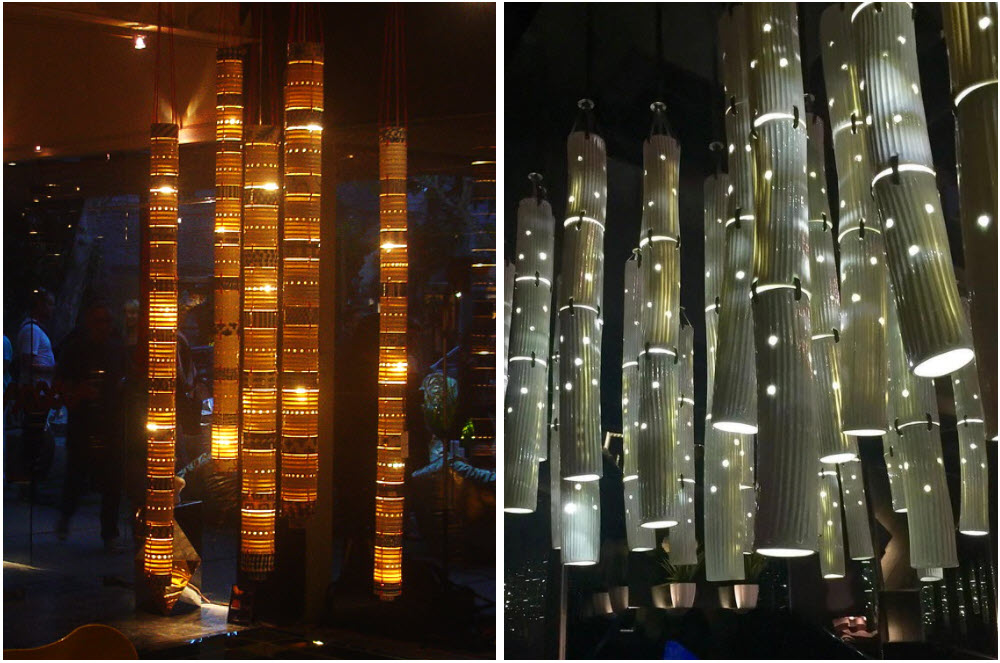

In August 2021 I ventured back into the studio. I had an upcoming exhibition and no inventory to look to. I gave myself permission to make whatever I wished to make and that included urns and other objects of contemplation as well as pots that would live part of their lives in the dish rack.

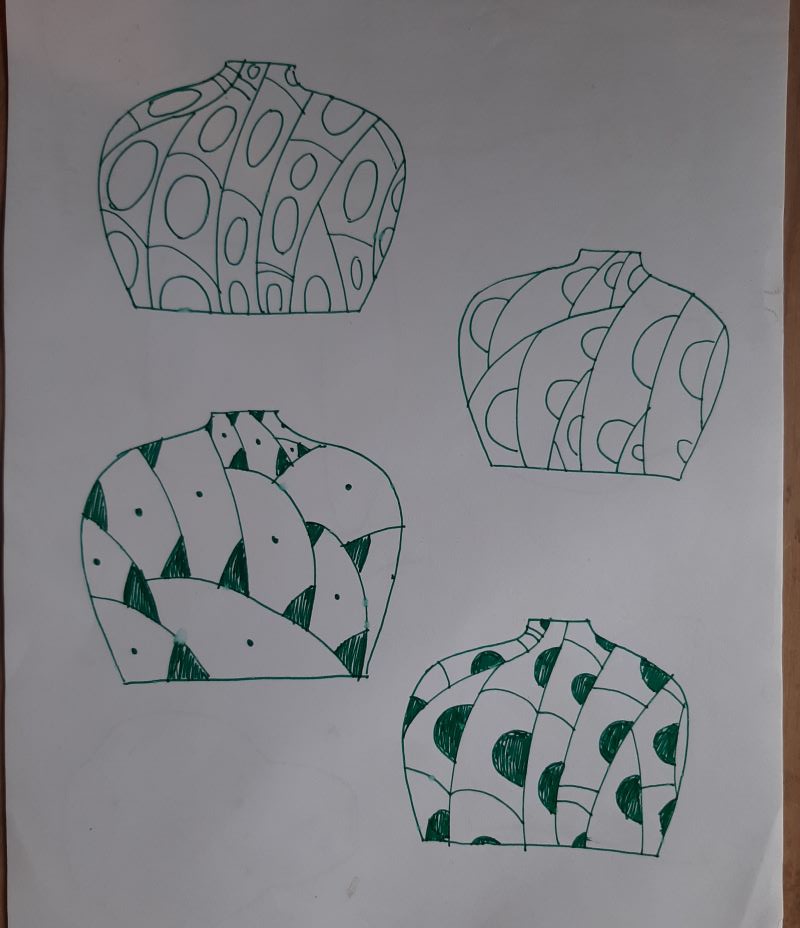

JW: Will you tell me a little about your creative process? Do you work out the form and decoration of a piece before working on it, or is your creative process more fluid and spontaneous, for example?

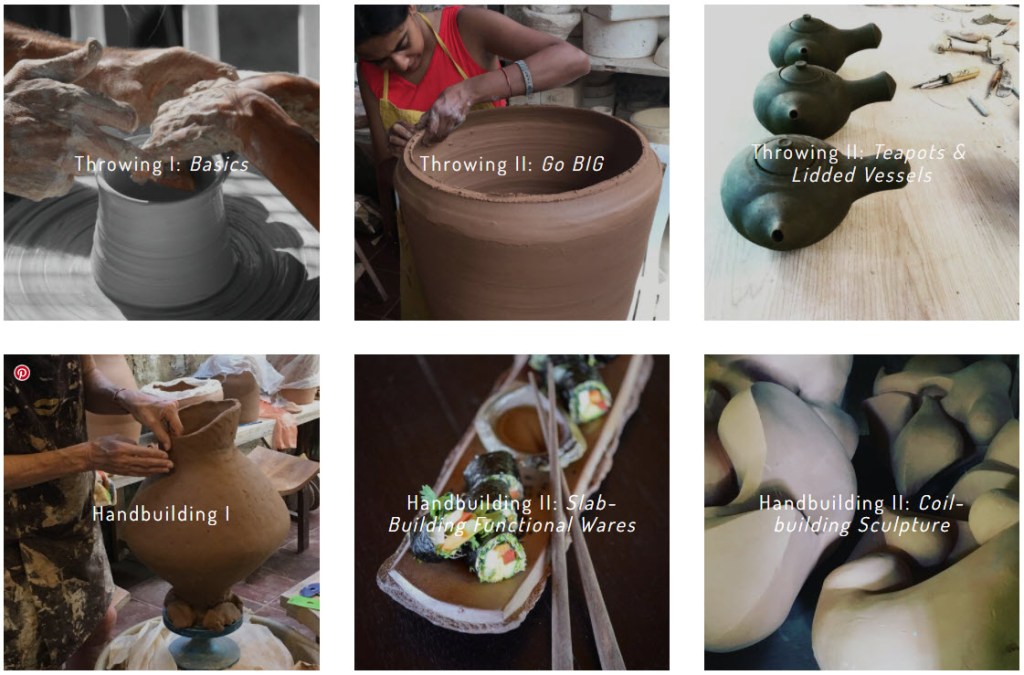

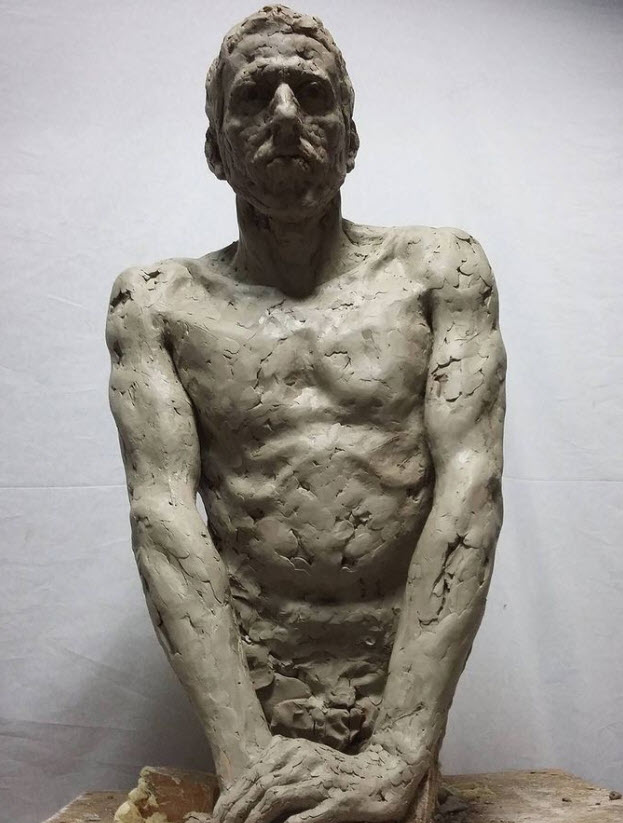

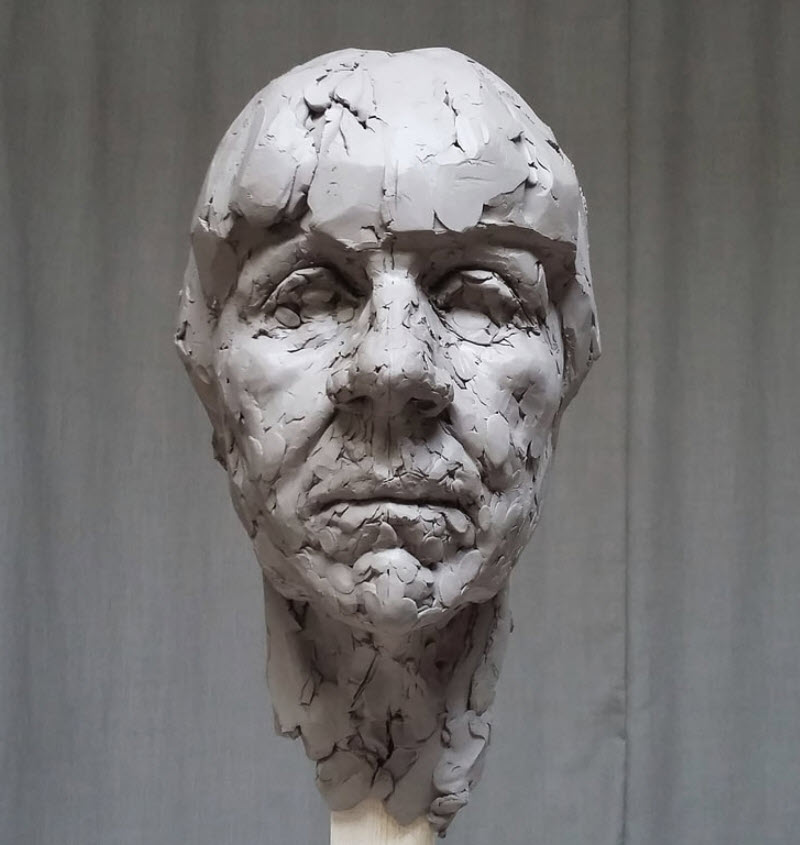

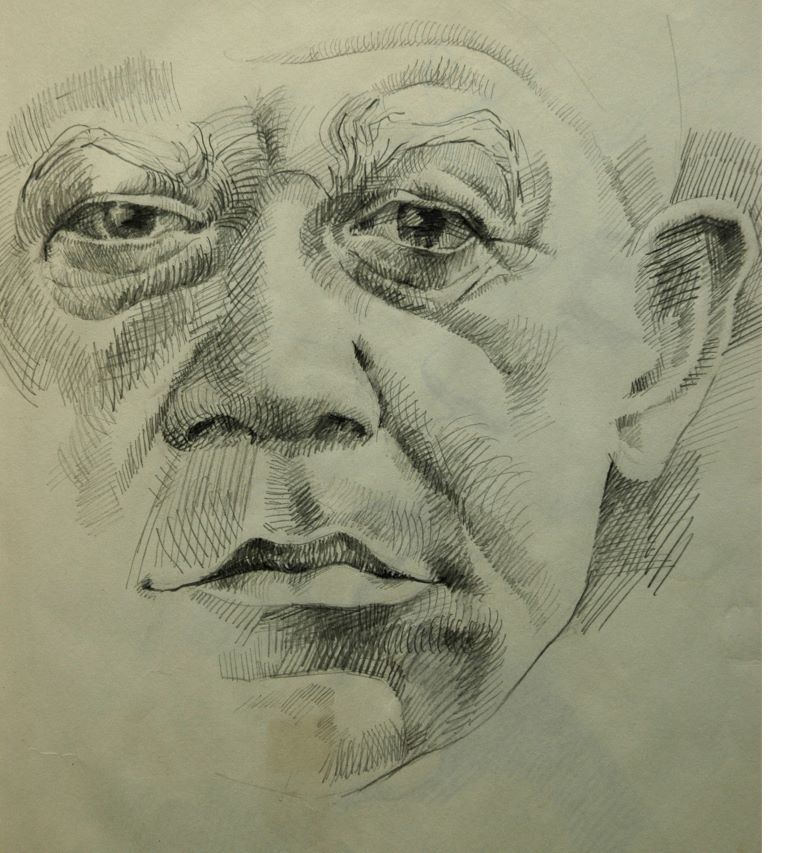

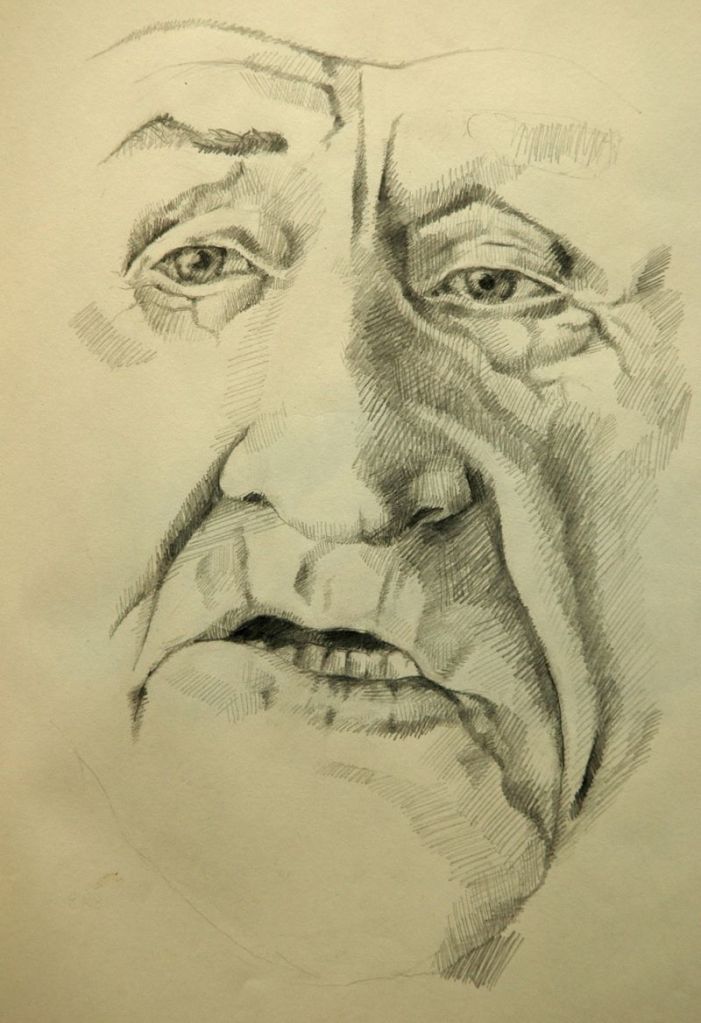

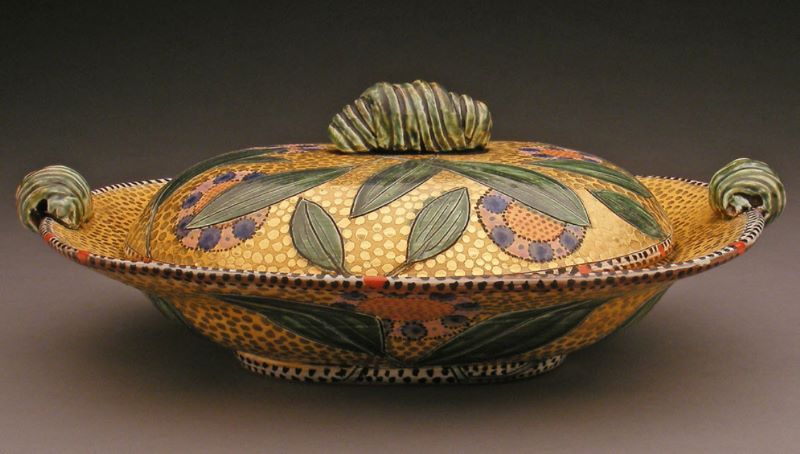

GK: I start a piece by determining whether I am making a plate, a cup, a covered form or something else. I “draw” in the air. I choose my approach: will I start with a mold, a soft slab, or coils? From there I build, examining the shape of a curve, the beginning points, the ending points, the lip edge. Eventually, things are made, bisque fired, glazed and fired, then china painted and possibly lustered and fired again.

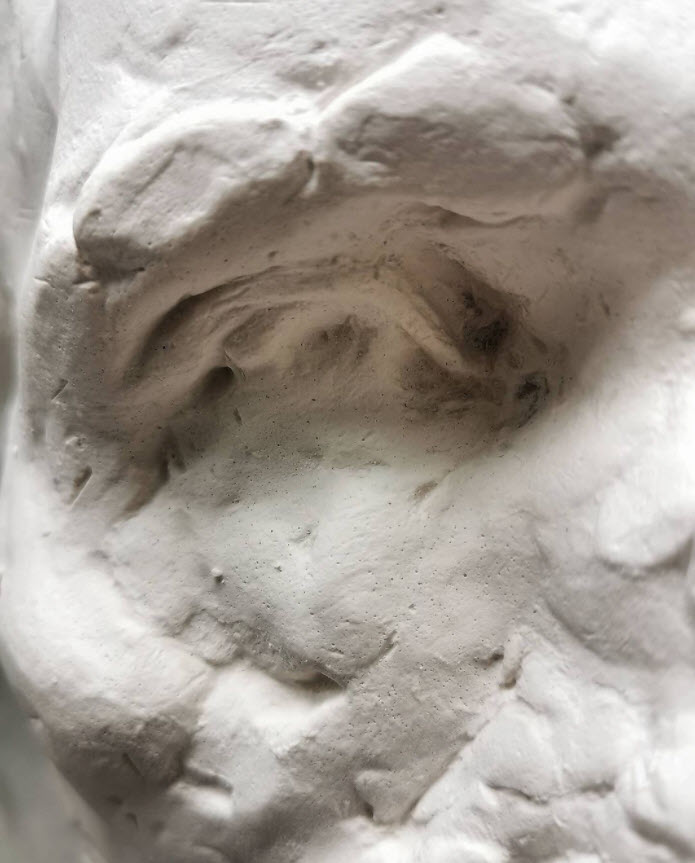

I use red earthenware clay and paint white slip on the leather hard forms in various ways. I am interested in layered surfaces and I achieve them, in part, by applying slips, glazes and the rest in a painterly manner. The surface is unregimented.

JW: How has your ceramic work evolved over time? What have you struggled with?

GK: The struggle I have dealt with in my career was finding my lifework within the medium. I believe it would have happened much sooner had I lived in Minnesota as an art student. There, functional pottery was what was happening. Before I took the plunge into functionality, I was making what I call “hand-built contemporary vessels”. I believe they were successful, but my problem, which I shall express simplistically, was that I became bored “by number seven in a series”. What was I bored with? Sticking with the content.

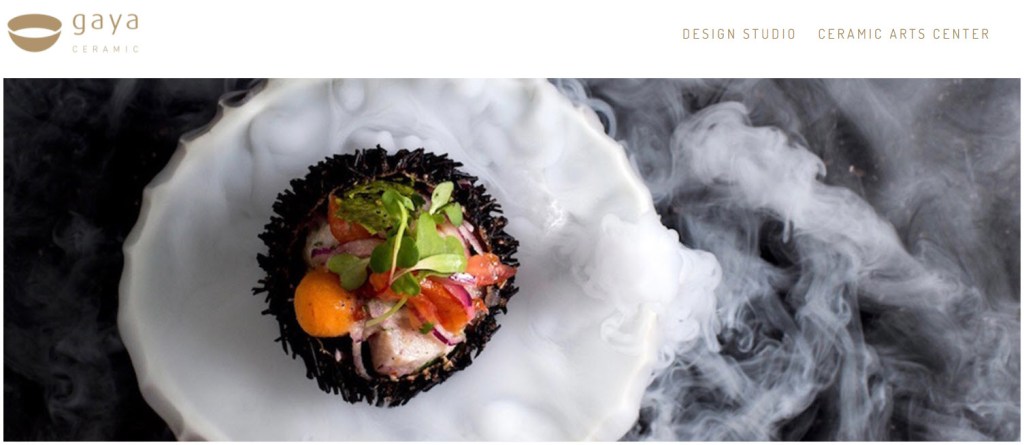

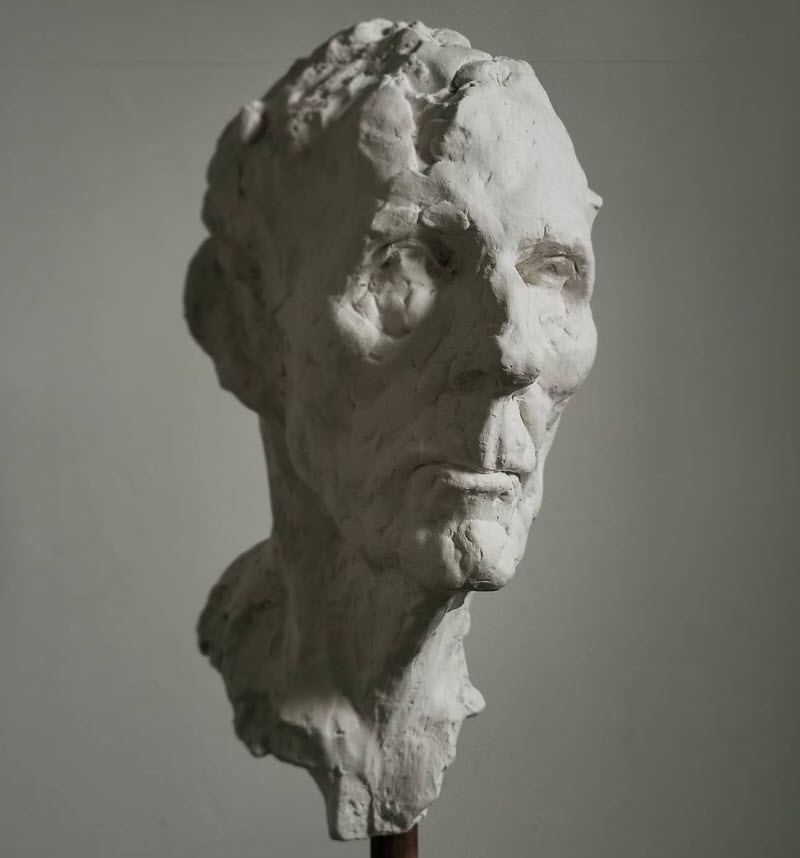

The magical joy of pottery is that the content is profound and is embedded in the forms. I, as an artist, do not have to explore and investigate any issue. I am a designer. The content is either metaphorical or quotidian depending on what I am making. An urn, a covered form, or the kind of vessel that in the past would have served in a meaningful, often religious ritual, is metaphorical. If I am making a plate, bowl, cup, then I am celebrating the quotidian: those essential needs of people for sustenance and community. I love that.

JW: What would you like people to know about you and your work?

GK: I have been the recipient of generosity from certain individuals in the field at seminal times in my career. I love teaching and mentoring and ended up with a fabulous academic job here in Nebraska. A job is fabulous if the boss is fabulous and my department chair was behind me all the way. I had two great colleagues, and we found in our separate ways, satisfaction and gratification in building program, facility, and in sharing times of frustration and times of joy.

I am an elder. My energy level is decreasing. My focus has moved from career to a larger canvas: family, pets, friends. I love the clay. I am proud of my work and excited by new developments. I don’t see that ending any time soon. I still have a difficult time taking no for an answer.

See more of Gail’s ceramics on her website.