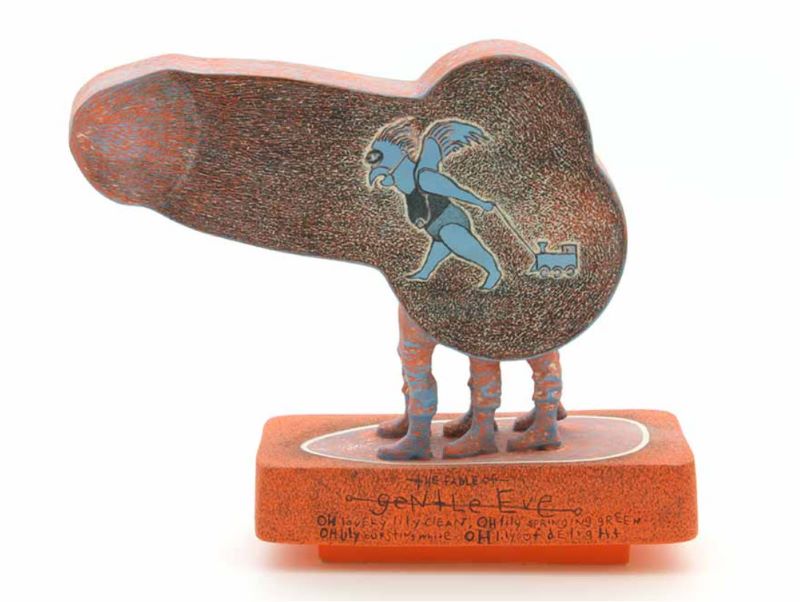

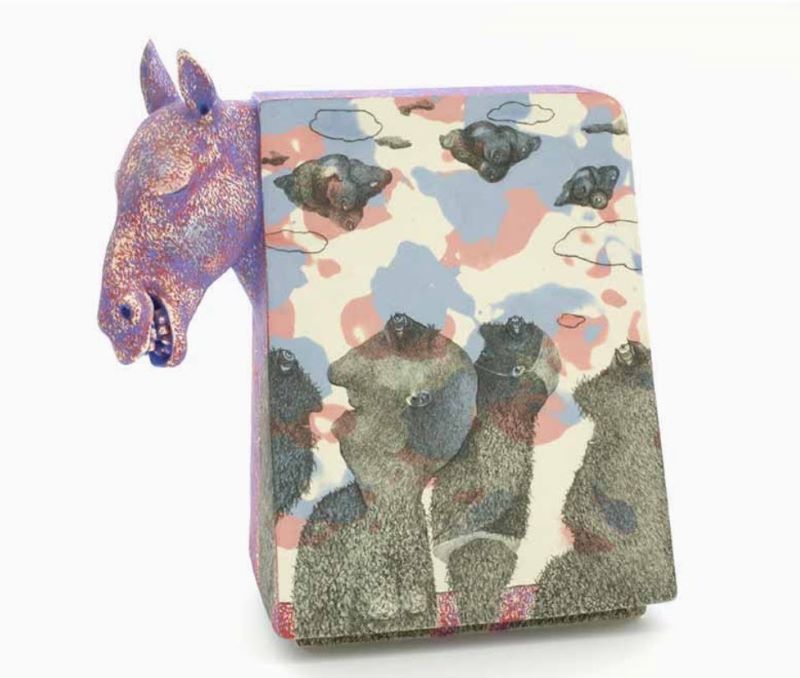

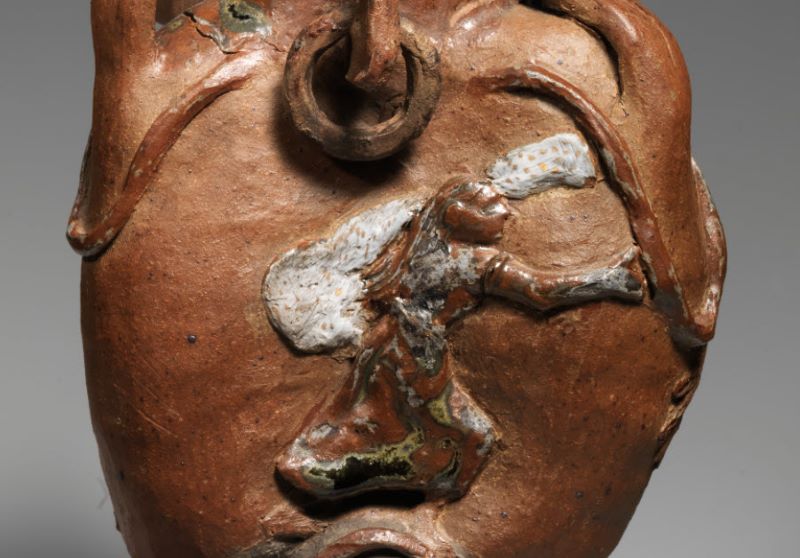

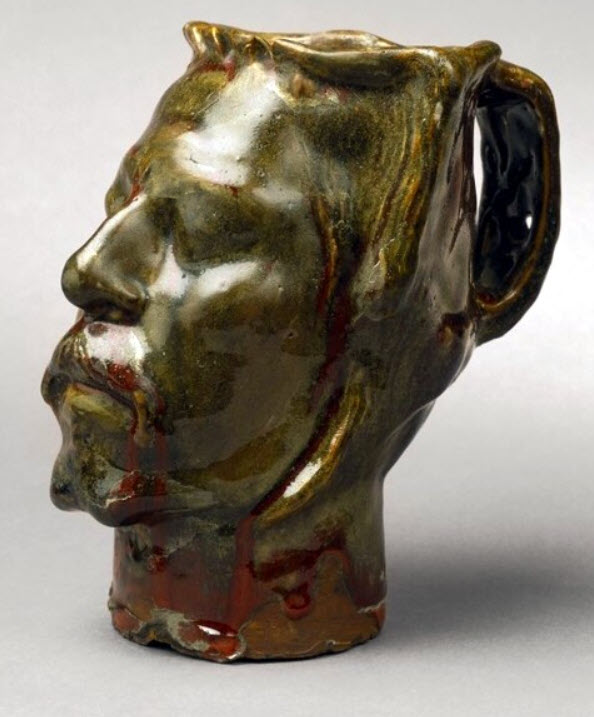

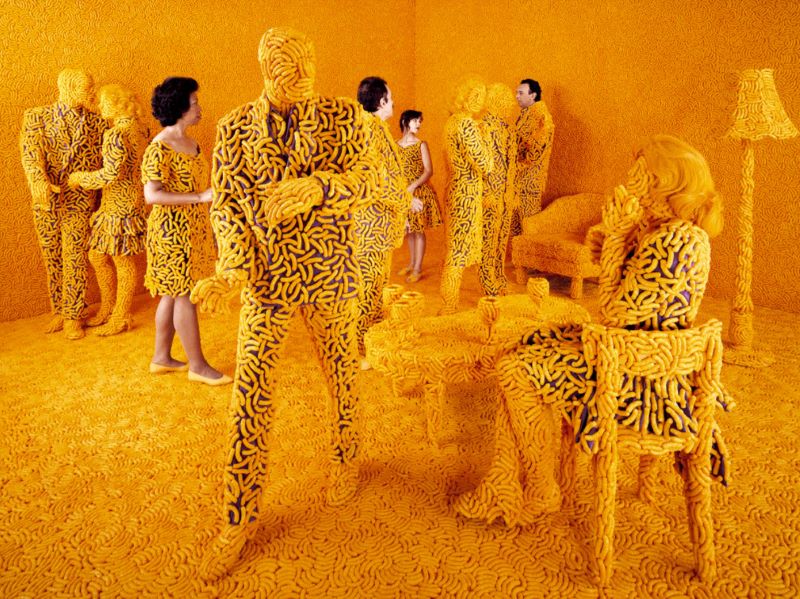

Lindsay Montgomery’s work punches pretty hard, there’s no doubt about it. She decorates her surfaces with narratives that harken back to historical periods and themes. She draws liberally from the past, and reformulates it into a contemporary vision. Her work is fun, vibrant, intriguing, irreverent, and memorable.

JW: In an earlier interview you describe your work as “neoisotriato” – drawing off 16th century Italian ceramics. Do you replicate techniques of that period in your process? Or do you refer mainly to the type of decoration and forms you employ?

LM: Yes, my neoistoriato works are made just as they were in the renaissance. I love Maiolica because it was invented to be a cheap knockoff of Chinese porcelain. It’s made with humble terra-cotta low-fire clay coated in tin-glaze so it can be painted and look like porcelain. It was sort of the knock off Louis Vitton handbag of its time, and I love that lower-class quality of it because I’m working class.

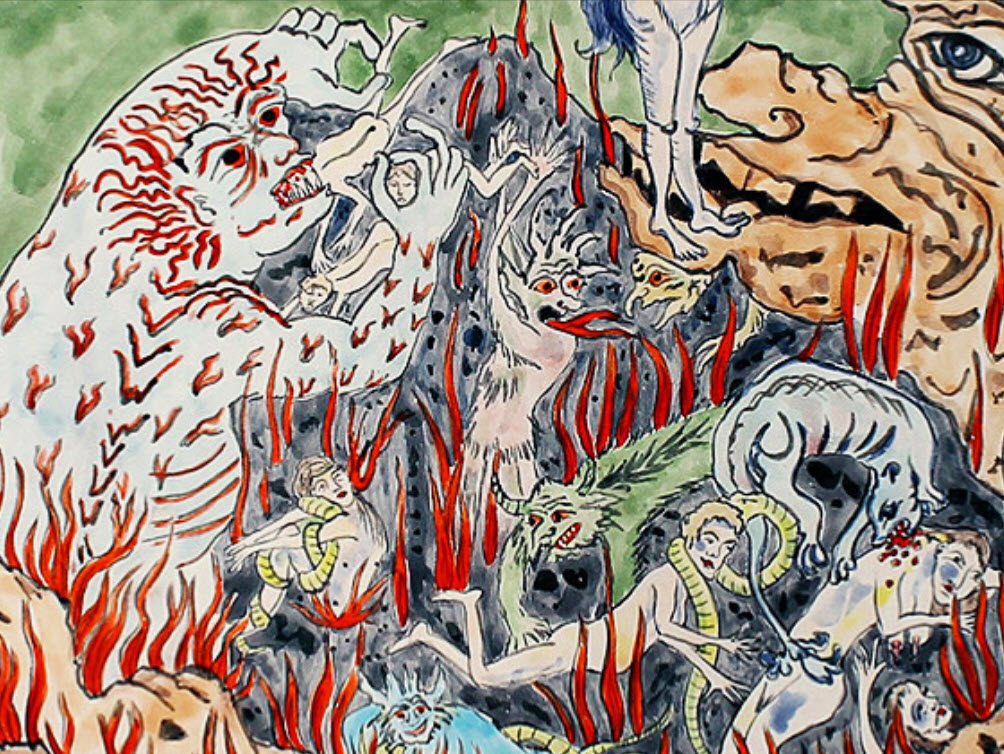

The historical forms are sumptuous and right for this kind of painting style so I riff on the historical works of not just Istoriato ware from Italy, but also French faience, Dutch delftware and English Staffordshire and other factory pieces. I like when the form and function of a piece adds to the story happening on the surface painting. Right now, I’m making censors with hell and hellmouth imagery, and I love how the smoke billowing out when they are in use adds authenticity and magic to the imagery.

JW: I’m also reminded of Bernard Palissy in some of the handles on your platters. Has he been an influence on your work?

LM: Oh absolutely yes! I love Palissy’s work because it kind of bridges the whole Maiolica to Majolica evolution of European tin-glazed earthenware. It’s beautifully painted and focused on the plate like the Italian Maiolica of the renaissance, but also has all the sculptural elements and juicy glazes that exemplify English Majolica from the 19th century. I also love the story of Palissy as an artist. His work was really punk-rock and genuinely freaked people out to the point where he became a pariah in society. He was an artist way ahead of his time. Snakes and the symbol of the serpent play a huge role in the forms and meaning behind my work as well, so Palissy’s work offers endless inspiration for the patterns and forms of snakes.

JW: How has the social turmoil caused by Covid influenced your work? I would think there are lots of stories that arose from the pandemic.

LM: My exhibition Year of the Flood that took place in 2021 in Quebec, was all about my experiences and feelings throughout the pandemic. My work feels extra urgent these days, and renaissance imagery is full of floods and fires and plague, so it’s eerie at times, the warnings of this moment we are living through have been there all along.

It’s really exciting to make the connections and find an image to work with that feels so perfect, and might have the power to help turn the direction we’re heading as a species.

JW: How has your work evolved since you started this type of neoisotraito painting in 2015? I’m seeing a lot of decorative elements like handles on your 2021 urns – and perhaps some large scale work.

LM: Yes for sure the pieces are getting larger and more ambitious in the painting and form as the series evolves. I think also in terms of the imagery that has gone through quite an evolution as well. When I started this series it was really about taking these historical images and re-arranging them to say what I wanted to say, or sometimes just showing it as it was so make a point about humanities lack of spiritual or moral evolution since the renaissance, where now I feel like I have been drawing these figures and this world for so long that I can create any scene I want.

The imagery has become its own world in my imagination that I can mine, and my hand is much quicker at translating my ideas.

JW: What about plans for the future? Do you have new directions you may take (process, forms, topics) in mind to explore?

LM: I’m excited to have a couple of residencies coming up where I can explore larger-scale works that would be too challenging to complete at my studio in Toronto. I’ve been working on a lot of individual pieces or series of pieces recently and I’m starting to think about something more specific. I have fantasies about being given a really specific historical space to respond to.

JW: You started off as a painter and that foundation is very evident in your ceramic work. Do you ever see yourself working as a “traditional” painter again? Or are there elements of ceramics that you can’t walk away from?

LM: I think at the end of the day I am a painter first, and all the reasons I got into ceramics were from a painter’s perspective. These days I don’t think too much about medium or catagories, in some ways what I am doing is working way more in a sphere of “traditional” painters then most of the painters I know.

I feel like I’m a painter and a sculptor, and when I make plates I’m tapping deeper into the painter, and when I make figurative work it’s more about the 3D. Who knows what the future holds, but I’m feeling good and satisfied with my process at this present moment and just wake up each day excited to continue on with my work.

JW: What would you like people to know about your work?

LM: I guess that there is a story behind each piece. I’m experimenting more with this recently, as social media gives me the opportunity to share the myriad of sources and images that make up a piece. It’s nice to be able to tell those stories with the work in a way that doesn’t feel stuffy or didactic, but more the casual way I would speak to someone about it at an opening or gathering.

More of Lindsay’s work may be seen at Cargocollecive.com/lindsaymontgomery.

Leah Sandals did an interview with Lindsay for CanadianArts, which you can find here. Maakemagazine, an online magazine, included another interview with Lindsay here.

NCECA profiled Lindsay as an emerging artist in 2019. An article (including a short video of a speech by Lindsay) is available here.